A top advisor to the president says she isn’t a feminist because she doesn’t hate men and she’s against abortion. An article in the Washington Post this morning quotes from her remarks at the annual Conservative Political Action Convention.

“It’s difficult for me to call myself a feminist in a classic sense because it seems to be very anti-male, and it certainly is very pro-abortion, and I’m neither anti-male or pro-abortion …. So, there’s an individual feminism, if you will, that you make your own choices. … I look at myself as a product of my choices, not a victim of my circumstances.”

The words are nothing new; her stance is nothing new. This sort of goading conservative figure in the media, the stereotypical outspoken female Republican, with her red power suit, dyed blonde hair, and outspoken feistiness, serves as a conservative symbol of feminine power but in reality acts to reinforce the male-centric status quo. Her appearance, the words she speaks, are all familiar.

Odd, though, are the echoes from a disparate world of activist women who also reject the label “feminist.” You wouldn’t expect alliances between those groups, yet both distance themselves from a label loaded with political and ideological baggage. There’s not much risk of a coalition, just a further reminder of the divisions that prevent women from coming together in the service of forward steps toward equity and justice.

Take out the references to abortion in the above quote and concentrate on the words “difficult for me to call myself a feminist in the classic sense” and it could almost be the 1980s and 1990s all over again. I heard similar sentiments all through those decades in the creative movements aligned with music, art, and political activism. Strong, powerful, outspoken women were quick to reject the label of “feminism” because of negative associations with the 1970s women’s liberation movement. They rejected the stereotype of the “bra-burner,” the image of femininity embodied by Gloria Steinem and Ms Magazine, and embraced a new ethos of feminine power.

In Seattle in the early to mid-90s I saw a surge of a new attitude in the younger women, much of it revolving around local and regional music scenes aligned with Seattle’s “grunge” scene and later, with the woman-centric Olympia-based Riot Grrl movement. The all-women grunge bands like Seven Year Bitch and L7 rejected notions of how girls should act, dress, and express themselves, performing alongside their male peers, while down in Olympia, bands like Bikini Kill and Sleater-Kinney put forward a fierce feminism outside of the rock-and-roll boys’ club. Seattle’s Stranger newspaper gave rise to female voices like columnist Inga Muscio, who wrote about messy subjects like abortion and menstruation and sex and later penned an influential book-length feminist manifesto, Cunt: A Declaration of Independence. The women of these scenes rejected attempts of their maternal elders to “rescue” them from the shackles of patriarchy and instead used those channels to claim power over men in order to lift themselves out of oppression. They celebrated their bodies, gloried in their flaws, flaunted their sexuality, and capitalized on their sexual power to survive and thrive in a man-centric world. No, they would not shut up. They were sick of shutting up. They would shout out their grievances in full-throated strident caterwauls, proclaim themselves sluts, glory in the parts of themselves that weren’t pretty and weren’t nice, live their lives how they chose, man or no man.

This brand of empowered woman is beyond the understanding of the spokesperson mentioned above and of the men whose agenda she is pushing. The aide in the red power suit operates in a sphere that dismisses the very real challenges and obstacles women face in the workplace and in the world. Her platform does little to advance the rights and protections of women and quite a lot to roll back hard-won protections. Her point of view profits from old-guard male mentality intended to keep women in line—square within the traditional roles prescribed for them by eons and eons of male governance. A woman who won’t behave, who upends victimhood and claims the ugliness in the names she’s called, is a problem for the status quo, because she rejects the framework altogether.

The textbook definition of feminism, “the advocacy of women’s rights on the basis of the equality of the sexes,” seems an innocuous enough starting point for common ground among women, but the term continues to inflame divisions and create impressions that are at best wildly exaggerated and at worst outright false and deceptive.

Some women are called to action at an individual breaking point—that moment or event that causes a woman to finally shout, “Enough!”—while others are content to accept the ages-old lot in life. Women claim a diverse array of beliefs and identities in 2017. Some strong women claim the tag “feminist” proudly; others reject it outright or find it “problematic.” There is no set prescription for who fits in that box, or even what it contains.

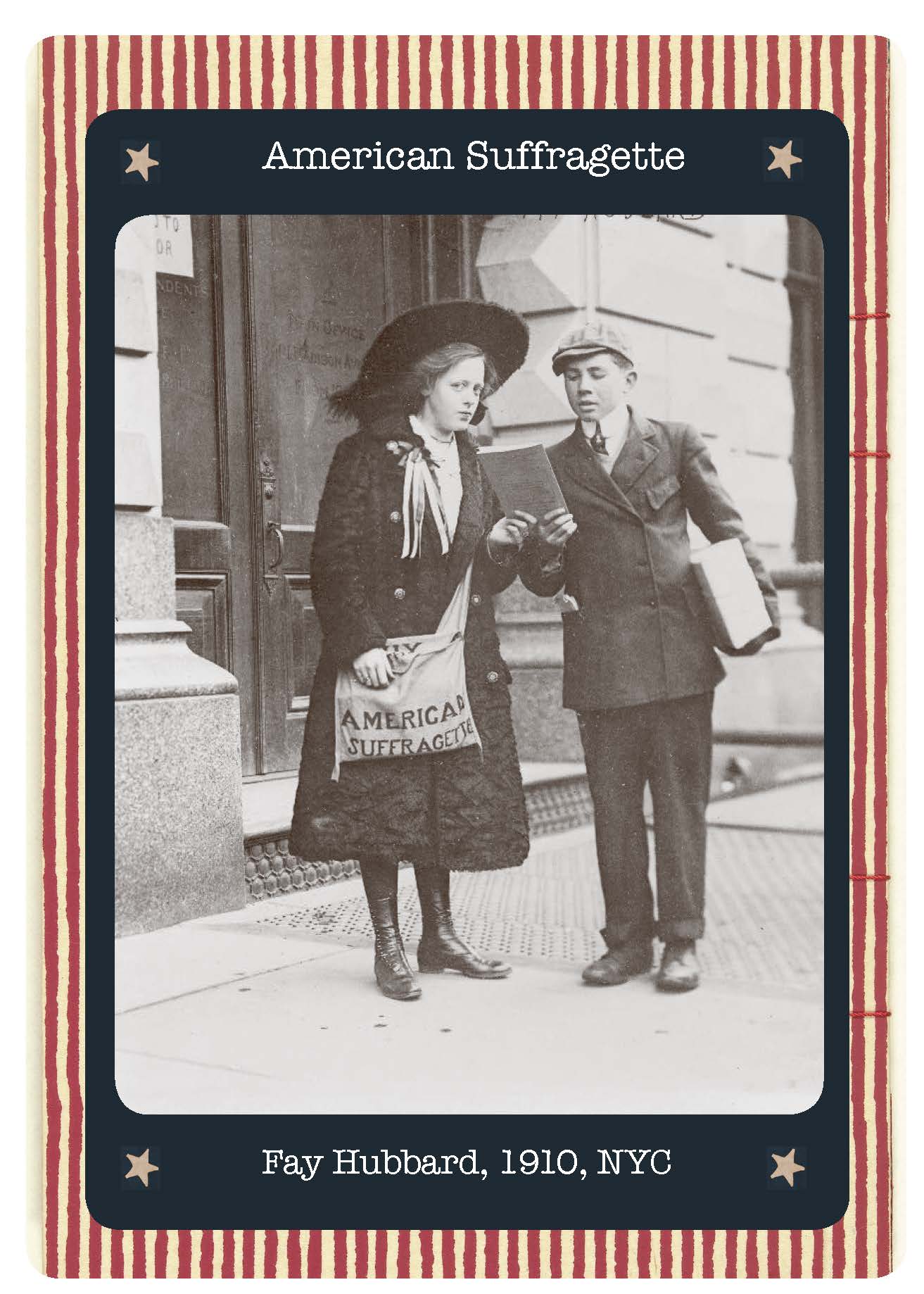

Photo: Fay Hubbard, 19-year old suffragette, full-length portrait, standing, selling suffragette papers. New York, 1910. Feb. 9. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/92510578/. Photo illustration: DePue, with background texture from Rijksmuseum.

Source Reading

Conway: ‘Classic’ Feminism Seems ‘Anti-Male’ And ‘Pro-Abortion’ Talking Points Memo

Cunt: A Declaration of Independence, Inga Muscio

Grunge: Music and Memory; Catherine Strong